Mahayana Buddhism is the largest Buddhist sect in the world, and its beliefs and practices are what most non-adherents recognize as "Buddhism" in the modern era. It developed as a school of thought sometime after 383 BCE, possibly from the earlier school known as Mahasanghika, though that claim has been challenged.

Mahasanghika ("Great Congregation") was an early Buddhist school that developed after the Second Buddhist Council of 383 BCE when the Sthaviravada school ("Sect of the Elders" or "Teaching of the Elders") broke away from the Buddhist community over doctrinal differences. This early schism led to others and the development of many different Buddhist schools of which Mahasanghika was only one.

Mahasanghika, claiming to represent the majority of Buddhists (as its name suggests) was thought by 19th-century scholars to have eventually become Mahayana ("The Great Vehicle"), but modern scholars contend that this is incorrect as evidence suggests Mahayana existed alongside Mahasanghika and was supported and encouraged by that school. How and why Mahayana Buddhism developed is a question still debated by scholars and Buddhist theologians.

Buddha’s Life & Death

According to Buddhist tradition, the belief system was founded by a former Hindu prince, Siddhartha Gautama (l. c. 563 - c. 483 BCE), whose father protected him from experiencing any kind of pain or suffering for the first 29 years of his life. When the prince was born, a seer prophesied that, should he ever experience or even see evidence of pain and suffering, he would become a great spiritual leader, renouncing his kingdom. Siddhartha’s father, hoping to preserve his dynasty, constructed a pleasure palace, which distanced his son from the everyday world of pain and disappointment and kept him safely inside the compound through the help of his many servants.

Siddhartha grew up, married, and had a son, all the while believing he was living in the real world. Periodically, he would be taken for a ride around what he believed was his father’s kingdom by a coachman loyal to the king who made sure to stay away from the gates leading to the outside world. One day, though, this coachman (or, in the most popular version of the tale, a substitute who was unaware of the rules) took the prince out through one of the gates, and he encountered the Four Signs that would change the direction of his life:

- An aged man

- A sick man

- A dead man

- An ascetic

He had never experienced anything like this before and questioned the coachman each time after seeing the first three, asking, "Am I, also, subject to this?" The coachman explained how everyone grew old, experienced illness and pain, and eventually died. This revelation horrified the prince because he understood he had been living in a false world constructed by his father which was actually governed by the same rules as this real world he was now encountering and, eventually, he would lose everything he loved.

The fourth sign, the ascetic, intrigued him, however, as this man seemed unconcerned with age, sickness, or death and so he had the coachman stop so he could ask why. The ascetic replied that he was living a life of non-attachment to the world and was at peace, and shortly after this, Siddhartha abandoned his life and fled to the woods to join a band of spiritual ascetics.

He learned meditation techniques and how to fast and various methods of spiritual discipline, but none of these satisfied him. Finally, he removed himself from the ascetic community and went out on his own, eventually seating himself beneath a Bodhi tree and claiming he would attain enlightenment there or die in the attempt.

Enlightenment came in the form of the Four Noble Truths:

- Life is suffering

- The cause of suffering is craving

- The end of suffering comes with an end to craving

- There is a path which leads one away from craving and suffering

He understood that the suffering he felt at the thought of losing everything he loved was caused by the desire that these things remain just as they were forever. This craving for permanence in an impermanent world, he realized, could only lead to suffering because the nature of life was transitory. All aspects of existence were in a constant state of change, growth, and dissolution; nothing could be held and claimed as everlasting, not even the identity one believed was oneself. Scholar John M. Koller comments:

The Buddha's teaching of [the Four Noble Truths] was based on his insight into interdependent arising (pratitya samutpada) as the nature of existence. Interdependent arising means that everything is constantly changing, that nothing is permanent. It also means that all existence is selfless, that nothing exists separately, by itself. And beyond the impermanence and selflessness of existence, interdependent arising means that whatever arises, or ceases, does so dependent upon conditions. This is why understanding the conditions that give rise to [suffering] is crucial to the process of eliminating [suffering]. (64)

In this moment, he became the Buddha ("Enlightened One") and recognized, in the Fourth Noble Truths, the way to live without suffering. He called this “the middle way” between extreme asceticism and enslavement to sense attachments, also known as the Eightfold Path:

- Right View

- Right Intention

- Right Speech

- Right Action

- Right Livelihood

- Right Effort

- Right Mindfulness

- Right Concentration

By following this path, one could still appreciate all that one had without insisting on permanence; one could appreciate without attachment. Buddha’s first sermon outlined this vision and attracted adherents who became the first Buddhists.

Early Buddhist Schools

Buddha taught his precepts until the age of 80 when he died. He told his disciples they should not choose a leader, every person should seek enlightenment individually just as he had done, and requested that his remains be placed in a stupa at a crossroads, presumably so travelers would see it and be reminded that there was a way to live without constant suffering through rebirth and death in countless incarnations. His disciples, instead, divided his remains amongst themselves and erected stupas at various locations throughout the region each felt most appropriate. They then institutionalized the Buddha’s teachings, chose a leader, and wrote up rules and regulations for the faith.

The First Council was convened c. 400 BCE at which the rules governing the community (the sangha) were established and the Buddha’s "true" teachings separated from "false" legends that had already grown up around him. At the Second Council of 383 BCE, different factions within the sangha offered their own interpretations of these teachings and of the rules previously agreed to. Disagreements led to one group, later known as the Sthaviravada school, separating from the main body and declaring they, alone, understood Buddha’s vision. The larger group became known as Mahasanghika – the Great Congregation – which had more adherents than Sthaviravada – and also claimed it alone understood the Buddha’s message.

The Sthaviravada school took Buddha’s admonition that each person should seek their own enlightenment and turned their focus inward toward each member of the sect working to become an arhat (saint) with no responsibility for anyone else. Mahasanghika took the example of Buddha’s life – complete selflessness in service to others – as their model and believed each person could become a Bodhisattva (“essence of enlightenment”) and it was a Buddhist’s responsibility, after attaining enlightenment, to help others achieve the same state.

More schools developed out of these first two and, by the late 3rd century BCE, there were many which included Mahayana. Around 283 BCE, the Mahasanghika school divided over whether the teachings of Mahayana were worthy of acceptance. Sometime shortly after this, Mahasanghika either died out or merged with Mahayana. It is unclear what happened to the school, but later texts state that they lost the authority to ordain monks which must have meant that some larger and more powerful school of thought now claimed that right. The only school with that kind of power at the time was Mahayana.

Mahayana Beliefs

The claim that Mahayana developed from Mahasanghika is supported not only in the similarity of the names (both claiming to be the largest group of believers and therefore the majority who agreed on Buddha’s vision) but by what is known of Mahasanghika beliefs later held by Mahayana. Mahasanghika rejected the Sthaviravada position that the primary goal of Buddha’s message was individual spiritual perfection, claiming an arhat was just as fallible as any other human being and possessed no supernatural powers or insights. To the Mahasanghika school, an arhat was simply a spiritual ascetic who used Buddha’s vision as a guide toward spiritual development instead of one of the many others in use at the time. Mahasanghika also believed:

- Bodhisattvas take vows prior to their incarnation to be born in the worst locales so they can help people overcome their suffering.

- Only the present exists at all times; past and future are illusions which distract and trouble the mind.

- Enlightened beings, spirits, and deities exist in every direction, at all times, because there actually is no time – no past and no future – only an eternal present.

- Enlightenment brings supramundane powers including the ability to communicate without speech.

Mahayana Buddhism accepted all of these tenets but also claimed that a Mahayana sutra – a book of Buddhist teachings, words of the Buddha, hagiographies, and meditative verses – represented the authentic vision of the Buddha while those of other schools, however valuable they might be, did not. The term Mahayana was self-applied – the school itself claimed to have the largest number of followers – and they called other schools Hinayana ("The Lesser Vehicle") applied to those groups that rejected Mahayana sutras and maintained their own beliefs regarding the Buddha and his essential teaching.

The main difference between Mahayana and other schools was their focus on the importance of the bodhisattva. One’s path toward enlightenment was not for one’s benefit alone but for the whole world. Once one had attained an awakened state, it was one’s responsibility to assist others in doing the same. A further important difference is that Mahayana understands the Buddha (known as Sakyamuni Buddha) as an eternal, transcendent being who is either eternal or is possessed of so long a lifespan that he may as well be. Accepting this truth and dedicating oneself to emulation of the Buddha’s path is rewarded by spiritual merit which advances one on the path to becoming a bodhisattva and then a Buddha like Sakyamuni and the many others that Mahayana believes came before and after him.

All Buddhas who have ever lived have always existed and will always exist in the eternal present human beings experience as life. Sakyamuni Buddha, therefore, did not actually die of dysentery after eating his last meal but only appeared to because those around him understood death as an end to life. They experienced the Buddha’s death because they accepted the paradigm of someone dying, but to the Mahayana school, this was only another of the many of life’s illusions. Sakyamuni Buddha, like all others, has been active in the lives of believers and non-believers the world over for centuries and will continue to be for generations yet to be born.

Mahayana Practices

These beliefs are observed in one’s daily life through the ten practices known as pāramitā (Sanskrit for "perfection") essential to one’s spiritual development:

- Dāna Pāramitā: Charity, the act of giving generously

- Śīla Pāramitā: Morality, self-discipline, virtuous conduct

- Ksānti Pāramitā: Patience, forbearance, endurance

- Vīrya Pāramitā: Effort, diligence, perseverance

- Dhyāna Pāramitā: Concentration, single-mindedness

- Prajñā Pāramitā: Wisdom, spiritual knowledge tempered by compassion

- Upāya Pāramitā: Method, the right way to accomplish anything

- Pranidhāna Pāramitā: Resolution, determination in working toward a goal

- Bala Pāramitā: Spiritual power

- Jñāna Pāramitā: Knowledge, both of the nature of life and of oneself

There are different paramita lists, some only include the first six of the above, some all ten. It should also be noted that the above is the list from Sanskrit sources while in the Pali sources (in which the pāramitā are known as pāramī) the perfections are different and include renunciation and a commitment to telling the truth at all times. The list of ten practices, eventually split into six and four, is thought to reflect an early cohesion of Buddhist thought, which fractured as different schools developed.

By including these practices in one’s daily life, one advances along the path of the bodhisattva. Scholars Robert E. Buswell, Jr. and Donald S. Lopez, Jr. comment:

The practice of these perfections over the course of the many lifetimes of the bodhisattva’s path eventually fructifies in the achievement of Buddhahood. The precise meaning of the perfections is discussed at length [in Buddhist commentary] as is the question of how the six (or ten) are to be divided between categories of merit (Punya) and wisdom (Jnana). (624)

The accumulation of spiritual merit is an important aspect of Mahayana belief and is accrued through adherence to the discipline of the paramita and acceptance of the truth of the Mahayana sutras.

Mahayana Scriptures

Besides the Dhammapada, a collection of 423 verses attributed to Sakyamuni Buddha, the foundational text of Mahayana Buddhism is The Perfection of Wisdom (the literal translation of the Sanskrit title Prajñāpāramitā) written by various Buddhist sages primarily between c. 50 BCE - c. 600 CE. It is a kind of manual on how to become a bodhisattva with a full understanding of Buddhist Dharma (“cosmic law”) unimpeded by one’s ego which darkens understanding through willful ignorance and pride. The verses of this work aim at confusing rational thought and linear thinking in order to free the mind to understand the world from a different, higher perspective.

For many people, this is the most important work in Buddhism, memorized and recited daily by Buddhists around the world. It contains some of the most famous Buddhist sutras such as The Perfection of Wisdom in Eight Thousand Lines (c. 50 BCE), The Diamond Sutra (c. 2nd century CE), and the Heart Sutra (c. 660 CE). The Heart Sutra is the most often memorized and recited as it focuses on discarding the ego-attachment to the identity one calls the "self", freeing the mind and spirit to create space – emptiness – in the self that can then be filled by higher thought and clearer vision. As long as one is full of oneself, one has no room for anything else – like a home that has become cluttered with so many possessions there is no room for even one more and, further, one no longer even knows what is there – but by reciting the Heart Sutra, one removes, piece by piece, the elements of self and "cleans house", as it were, restoring a natural balance and order to one’s life.

There are many more significant scriptures in Mahayana Buddhism including the equally, if not more, famous Lotus Sutra (also known as Sutra on the White Lotus of the True Dharma) which makes clear that all forms of Buddhism are aspects of Ekayana ("One Vehicle" or "One Path") and Mahayana Buddhism, while still claiming to be the most complete or authentic, is only one of many.

There are also the Pure Land Sutras, celebrating the work of the Celestial Buddha Amitabha and the realm of bliss he created, which awaits believers in the afterlife. The Golden Light Sutra emphasizes the importance of order in one’s internal life that is reflected externally, specifically concerning kings and those in authority. Another work, the Tathagatagarbha Sutras, makes clear that all living things are possessed of a Buddha-nature which, if developed, lead to the enlightenment of Buddhahood. Other, equally important, sutras, develop these themes and others in providing a complete guide to following the path of the bodhisattva and freeing oneself, and then others, from ignorance, avarice, and the craving that binds one to the wheel of perpetual suffering.

Conclusion

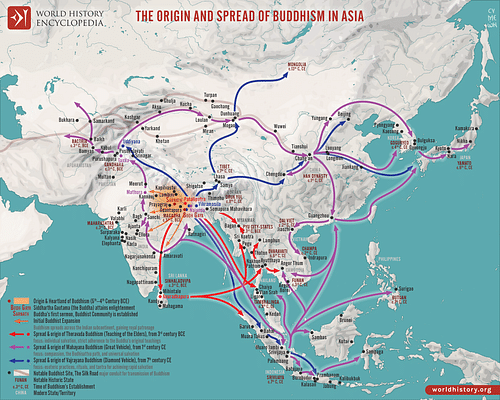

Buddhism did not initially find a wide audience in India where Hinduism, which was already well established, and Jainism, which appealed to the ascetic community, were more popular. It was not until Buddhism was embraced by Ashoka the Great (r. 268-232 BCE) of the Mauryan Empire (322-185 BCE) that it was spread across the Indian subcontinent and was exported to other lands such as China, Sri Lanka, Korea, and Thailand.

In the present day, there are many schools of thought around the world representing the Buddhist vision but the main three are:

- Mahayana Buddhism

- Theravada Buddhism (The School of the Elders, possibly developed from the Sthaviravada school)

- Vajrayana Buddhism (The Way of the Diamond, also known as Tibetan Buddhism)

Of these, as noted, Mahayana Buddhism is the most widely practiced, and its rituals, such as pilgrimage to stupas and other holy sites and veneration of statues of the Buddha, are most widely recognized. Contrary to claims by some modern writers, Theravada is not the oldest school of Buddhism as it developed at the same time as Mahayana. All schools recognize the value of Buddha’s essential teaching of the Four Noble Truths and the Eightfold Path but interpret and express that value differently in the way they think best to address suffering and encourage compassionate enlightenment throughout the world.